By David Bressan

]…we expected to unearth a quite unprecedented amount of material – especially in the pre-Cambrian strata of which so narrow a range of antarctic specimens had previously been secured. We wished also to obtain as great as possible a variety of the upper fossiliferous rocks, since the primal life history of this bleak realm of ice and death is of the highest importance to our knowledge of the earth’s past.”

This week we remembered the struggle and final triumph to reach one of the last large white spots of the globe: the interior of the southern continent of Antarctica. 100 years ago only segments of the coast and the approximately contours of Antarctica were known – a perfect scenario for the imagination of writers. In 1888 the novel “A Strange Manuscript Found in a Copper Cylinder“, by Canadian James De Mille, was posthumously published (Brian Switek recovers these lost tales on his Dinosaur Tracking post “Who Wrote the First Dinosaur Novel?“). The novel narrates the adventures of a sailor shipwrecked on an unknown part of the Antarctic continent, where volcanic activity enables a tropical lost world to flourish. Only in 1912, maybe also in response to the successful expeditions to the South Pole, Arthur Conan Doyle reinvented “The Lost World” in a remote region of the Amazonian forest. Curiously Edgar Rice Burroughs published in 1918 the first part of “The Land That Time Forgot“, maybe hoping to exploit the celebrity of Doyle’s tale. Here the primordial world populated by tropical forests and of course dinosaurs is located again near Antarctica on the island of Caprona, first reported by the (fictitious) Italian explorer Caproni in 1721.

“At the Mountains of Madness” is a science-fiction/horror story by the American writer H. P. Lovecraft (1890-1937), written in February/March 1931 and originally published in the February, March and April 1936 issues of one of the first pulp-magazine of history: “Astounding Stories“.

Like many others stories by Lovecraft also Mountains of Madness is retold from a first-person perspective: Geologist William Dyer is one of the few survivors of an Antarctica expedition that in 1930 studied the geology of the frozen continent. After discovering strange trace fossils a team ventures into the unknown interior of Antarctica, only to discover a terrifying chain of dark peaks:

“He was strangely convinced that the marking was the print of some bulky, unknown, and radically unclassifiable organism of considerably advanced evolution, notwithstanding that the rock which bore it was of so vastly ancient a date – Cambrian if not actually pre-Cambrian – as to preclude the probable existence not only of all highly evolved life, but of any life at all above the unicellular or at most the trilobite stage. These fragments, with their odd marking, must have been five hundred million to a thousand million years old.”

Lovecraft is today considered one of the first authors to mix elements of the classic gothic horror stories, mostly characterized by supernatural beings, with elements of modern science-fiction, were the threat to the protagonists results from natural enemies, even if these are creatures evolved under completely different conditions than we know. He was an enthusiastic autodidact in science and incorporates in his story many geologic observations made at the time, he even cites repeatedly the geological results of the 1928-30 expedition led by Richard Evelyn Byrd.

Only in 1929-31 the British-Australian-New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition was mapping the last unknown coastlines and still not much was known about the geology and palaeontology of the interior of the continent.

The first fossils, fragments of petrified wood, described from Antarctica were collected in 1892-93 on Seymour Island by members of the Norwegian Antarctic Expedition led by Carl Anton Larsen (most fossils were traded later by the sailors for tobacco, Larsen handled his specimens to the University of Oslo). One of the first geologists to collect fossils in Antarctica was the Swedish geologist Otto Nordenskjöld in 1902-03, he and his crew discovered Jurassic plant fossils, shells and the bones of gigantic penguins (which also have an cameo in Lovecraft’s tale). Based on the plant fossils Nordenskjöld was also one of the first researchers to propose that Antarctica in the past experienced a much warmer climate and was covered by forests of ferns and other tropical plants. Lovecraft will evocate this long lost past in his story by the unexpected discovery of a cave that acted as sediment trap for millions of years:

“The hollowed layer was not more than seven or eight feet deep but extended off indefinitely in all directions and had a fresh, slightly moving air which suggested its membership in an extensive subterranean system. Its roof and floor were abundantly equipped with large stalactites and stalagmites, some of which met in columnar form: but important above all else was the vast deposit of shells and bones, which in places nearly choked the passage. Washed down from unknown jungles of Mesozoic tree ferns and fungi, and forests of Tertiary cycads, fan palms, and primitive angiosperms, this osseous medley contained representatives of more Cretaceous, Eocene, and other animal species than the greatest paleontologist could have counted or classified in a year. Mollusks, crustacean armor, fishes, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and early mammals – great and small, known and unknown. No wonder Gedney ran back to the camp shouting, and no wonder everyone else dropped work and rushed headlong through the biting cold to where the tall derrick marked a new-found gateway to secrets of inner earth and vanished aeons.”

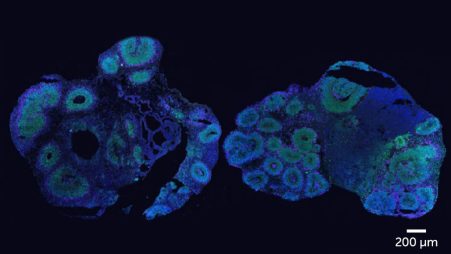

In 1920 the geologist William Thomas Gordon described the oldest Antarctic fossils, archaeocyathids found in rocks dated to the Cambrian Period (more than 500 million years ago). Archaeocyathids, sponge-like organisms, were also discovered in samples coming from a moraine of Beardmore Glacier and collected in 1907-09 by Ernest Shackleton during his failed attempt to reach the South Pole.

The desire to understand the ancient history of Antarctica had also a tragic consequence. December 14, 1911 Roald Amundsen and his team had reached the South Pole, four weeks later Robert Falcon Scott and his team sighted the tent with the Norwegian flag. This unexpected discovery demoralized Scott and his men who had also to face the impending polar winter and an insufficient stock of supplies. However Scott decided during his return to stop at a moraine and collected rock samples, loosing precious time and adding ulterior weight on the sleigh pulled by the men.

“The moraine was obviously so interesting that when we had advanced some miles and got out of the wind, I decided to camp and spend the rest of the day geologizing. It has been extremely interesting . . . Altogether we had a most interesting afternoon, but the sun has just reached us, a little obscured by night haze.”

The samples were discovered in 1912 along with the frozen bodies of the men. In 1914 British palaeontologist Albert Charles Seward described the fossil plant remains collected by Scott’s party as Glossopteris and Vertebraria, two species of plants distributed almost worldwide that will later be used by Alfred Wegener as evidence that Antarctica was once connected to the other continents.

Lovecraft apparently was fascinated by the theory of continental drift as proposed by Wegener in the 1920s, as he describes the discovery of an ancient topographic map of unknown origin in a dead city, showing the slow movement of the continents on the surface of earth.

“As I have said, the hypothesis of Taylor, Wegener, and Joly that all continents are fragments of an original Antarctic land mass which cracked from centrifugal force and drifted apart over a technically viscous lower surface- an hypothesis suggested by such things as the complementary outlines of Africa and South America, and the way the great mountain chains are rolled and shoved up-receives striking support from this uncanny source.”

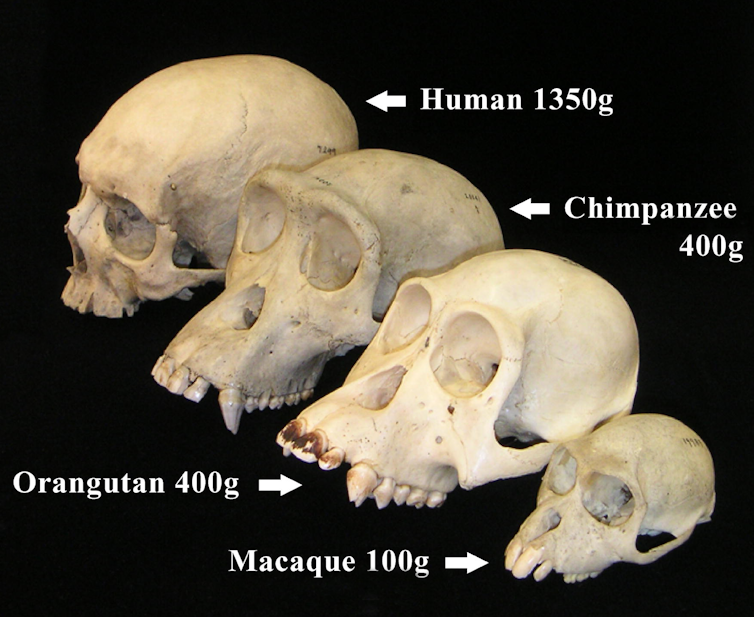

For Lovecraft the geology and the detailed description of the discovered fossils is an essential part to present the idea of deep time, especially the pre-Cambrian, when according to the knowledge of his time no life existed on earth. However the expedition of Dyer discovered in rocks dated to this ancient period the traces of highly evolved creatures, referred only as Elder Ones. They are far superior in their culture, technology and abilities to our civilization, most important they are immeasurable older than humans and Lovecraft’s tale ends with a warning: compared to the almost unimaginably vastness of the age of earth (and these creatures) we should feel quite humble (and afraid).

“I am forced into speech because men of science have refused to follow my advice without knowing why. It is altogether against my will that I tell my reasons for opposing this contemplated invasion of the antarctic – with its vast fossil hunt and its wholesale boring and melting of the ancient ice caps. And I am the more reluctant because my warning may be in vain.”

Today much more is known about the geology of Antarctica. The landmass of Antarctica is composed by two major geologically distinct blocks separated by the Transantarctic Mountains, a 2.800km long mountain range with 4.000m high peaks (Lovecraft´s imaginary Mountains of Madness were more than twice as high as these mountains).

East Antarctica is dominated by Precambrian igneous and metamorphic rocks, however almost completely covered by a 4.000 thick ice cap. Even if East Antarctica is thought to be an ancient and stable continental shield, geophysical investigations showed prominent mountains buried under the ice, like the Gamburtsev Mountain Range, a 1000km long mountain range with peaks almost 3.000m high. The origin of these unachievable mountains was for long time an intriguing mystery – volcanic origin, mountains formed by subduction very recently or the remains of an ancient Gondwanan orogeny were the most popular hypotheses. Most recent research (FERRACCIOLI et al. 2011) proposes that these mountains are much elder ones, formed by movements during the collision of the various Antarctic blocks.

West Antarctica is a mosaic of five smaller blocks covered by the West Antarctic Ice Sheet; however rocks are exposed on the Antarctic Peninsula. The Antarctic Peninsula was formed by uplift and metamorphism of sea-bed sediments during the late Paleozoic and the early Mesozoic, as proved by the fossils that inspired Lovecraft.

You must be logged in to post a comment.